RARE BREEDS TRUST OF AUSTRALIA

powered by TidyHQBlog

Blog

Supporting Cattle Breed Diversity in Australia

By Catie Gressier*

Over the past century, the goal of animal husbandry has shifted to increasing performance for economic gain. Cattle have been divided into dairy or beef breeds and are selectively bred for milk volume, or rapid growth and muscling, respectively. Production increases have been extraordinary, yet have come at a considerable cost.

The livestock industry’s favouring of a diminishing number of these high-yielding commercial breeds has resulted in the extinction of at least 184 cattle breeds globally. That is at least 17% of cattle breeds we’ve already lost. In Australia, around 83% of the dairy herd are now Holstein–Friesians and approximately 70% of the national beef herd is Angus. Twelve cattle breeds are now extinct, with another 38 listed as under varying levels of threat by the Rare Breeds Trust of Australia (RBTA).

This echoes a broader pattern of loss of our agricultural biodiversity, which poses a significant threat to food security. The shift to corporate ownership of certain seeds, breeds and bloodlines has resulted in the homogenisation of our diets globally. As Dan Saladino writes:

the source of much of the world’s food – seeds – is mostly in the control of just four corporations; half of all the world’s cheeses are produced with bacteria or enzymes manufactured by a single company; one in four beers drunk around the world is the product of one brewer; from the US to China, most global pork production is based around the genetics of a single breed of pig; and, perhaps most famously, although there are more than 1,500 different varieties of banana, global trade is dominated by just one, the Cavendish.

Alongside this loss of variety within our fruit and veg, crops and breeds, artificial insemination (AI) technology has resulted in a vast reduction of bloodlines within livestock breeds. This is evident in Holstein–Friesians, whose high milk yields have seen their popularity soar. In the US, over 90% of dairy cattle are Holsteins. In their research into male Holstein lines, researchers at Pennsylvania State University found that almost all AI Holstein bulls worldwide traced their lineage to one of two bulls born in the 1880s. Their lineages extend to two AI bulls born in 1960, from whom 99.84 percent of North American Holstein bulls are today descended. In terms of genetic diversity, these nine million cows are thus estimated to be equivalent to a herd of fewer than a hundred animals.

In Australia, with the cattle industry thriving, some might wonder whether this loss of breed and bloodline diversity matters. Given the speed of climatic and social change we currently face, I think allowing this loss of diversity constitutes an enormous gamble. Scientists have long understood that risk is mitigated by ensuring diversity at the genetic, species and ecosystem levels. And with cattle, the cracks are already beginning to show. The global dissemination of lucrative bloodlines has resulted in the spread of genetic defects, such as the case of Arthrogryposis Multiplex (AM) and Neuropathic Hydrocephaly (NH) in Angus cattle. Among Holsteins, the intensity of selection for milk volume has compromised other traits resulting in metabolic and structural problems, increased production disease prevalence, and reduced fertility and longevity in the breed. Moreover, Holsteins high milk outputs require high feed inputs, increasing negative ecological impacts.

On a big picture level, there are serious disease risks posed by a lack of biodiversity, especially when compounded by intensive animal confinement, where zoonotic diseases have ripe grounds for catastrophic outbreaks. Rob Wallace, an evolutionary biologist emphasises the need for ‘immunological firebreaks’ against disease pandemics. Such firebreaks emerge from a diverse gene pool and are embodied in certain breeds for certain pests and diseases.

Conserving breed and bloodline diversity not only mitigates against disease risks, but also ensures the perpetuation of a wide array of traits to meet the needs of future populations. Consumer preferences are always changing, as seen in the fixation of recent decades on lean meat and milk, which is now beginning to wane. It’s difficult to predict what trends will emerge in future, so conserving breed diversity keeps our options open. And, of course, breeds form a valuable part of our cultural heritage, with many of the old breeds who are currently at risk being docile, hardy, beautiful animals that have unique qualities and quirks that make them a pleasure to have around.

When I learned back in 2017 about the extinction crisis unfolding on our farms, I was shocked that more people weren’t talking about it. I designed this project to examine these issues and, in 2020, was awarded Australian Research Council funding for myself and two PhD students to spend three years working with the rare and heritage breed farmers conserving breed diversity across Australia. We’re over halfway through now, and within this rather dystopian story of extinction and loss, there are also many heartening success story.

So how to keep a marginal breed thriving? Everyone has their opinions, and there’s plenty of valuable debates to be had, but here are my thoughts based on what I’ve learned so far. Contrary to much of the discourse we hear from agribusiness, the Food and Agriculture Organization confirms that approximately 80% of the world’s food is produced on family farms. Family farms tend to be more ecologically sustainable, and foster more vibrant rural communities, while being home to greater wildlife variety and agrobiodiversity. Accordingly, growing the number of small-holders, rather than pursuing the get-big-or-get-out approach to farming of recent decades, seems the best way forward.

For the health of the animals and the planet, ensuring high animal welfare and good land stewardship are, of course, essential. Consumers are quite rightly increasingly concerned about these issues, and sharing knowledge with them about sustainable farming, the unique qualities of particular breeds, and the value of breed diversity is time well spent.

Maintaining the quality of animals is also key. Protecting bloodline diversity—especially when there’s a relatively small gene pool—is important, as is breeding for a balance of traits given the dynamic and unpredictable consumer market, and the risks of a narrow productivity focus. Making the hard decisions and ensuring faults are not bred into the herd—including not only issues related to conformation, fertility and performance, but also temperament—is critical for the long-term health and reputation of the breed.

Finally, perhaps the least acknowledged aspect of supporting breed longevity is the social component. Encouraging and mentoring young people to get involved with the breed builds a future pipeline of skilled breeders and handlers. At the other end, making plans for succession with your herd ensures unique bloodlines aren’t lost. Being inclusive and tolerant of different views, sharing knowledge and opportunities, and being one of, or offering support to, the hard-working volunteers who run the societies and shows are perhaps among the greatest gifts you can give the breed.

*Dr Catie Gressier is a Research Fellow in the School of Agricultura and Environment at the University of Western Australia, and a Director of the Rare Breeds Trust of Australia.

Survival Of The Fittest …

Musings About How a NFP Volunteer Organization Moves Forward Post Covid.

By Katy Brown, RBTA Director and Pig Coordinator

January 2022

For many years, like many like-minded people, I have served on committees and been a volunteer at many events. It’s what we do, it’s how we stay connected, it’s how we give back to our community. It’s also where I have met some of the best people you are ever likely to meet, people who share their time, knowledge, skills and resources, over and over again for the benefit of others and their cause. With me it is Livestock, mainly Horses and Pigs.

Some of the take home lessons are simple; the best volunteers are not self serving, they serve their association not their private interests, they willingly work as part of a team that is a shining light for the organization and like any good team allows people to express their strengths and it is incredible the skill-sets many volunteers bring to the table.

Anecdotally most volunteers on Show societies, Breed Societies, Field Days etc. are older people who have served for many years and come from a time when that is what you did, everything from scanning the showground surface for rocks or dangers, to making morning tea and lunches for judges and stewards. Most competitors don’t realize that within a week of most Agricultural shows finishing the committee is hard at it, reviewing and hoping costs were covered and ideally a profit banked. For the rest of the year the committee works towards the next show and I have helped on a committee where the average age was 75 with some closer to 85. Some have Awards in their name or Pavilions, or Life Memberships to pay homage to a lifetime of service to their association. But how do organization move forward now in a vastly changed environment. Many older volunteers from those in the op shops to the tea ladies at the hospital have had to cease as the over 70 population was deemed to have too greater risk from Covid. From people I have spoken to I understand this poses a loss of social contact and for some the even greater loss of the sense of being useful and contributing to make something better. As we move forward I believe that some of these older volunteers will cease to participate in such a changed environment. This is a huge loss both of historical knowledge and of hands on experience and often of teams built over decades.

I read an article prior to Covid lamenting that younger people are less likely to volunteer and many who have moved into what were rural areas are in estates that somewhat mimic a suburban lifestyle where they do not connect with the farming fraternity. Many commute so do not work in the area and often shop where they work, schools, local teams, local brigades all find it hard to recruit from this new population. I believe there are multiple reasons not in the least that people are busy .Covid slowed everyone down ...people felt isolated, lonely, without purpose, however our committees marched on embracing zoom or messenger apps and chatting from home probably far more often than in non Covid times. A lot got done, a lot got canceled, a lot was put on hold, but basically the end game was always in sight and without event deadlines many committees looked to do other things. Maybe online or virtual shows, webinars, a year book, an update of the website, embracing of more media platforms, we never stopped and as a result stayed engaged, enthused and in touch. A great gift when many floundered unused to having time.

So there begs the question ...when volunteering at any level can give you so much, why is it increasingly hard to get people to step up.

My second issue if we can call it that is the attitude when people make a request to a volunteer organization for something. What is the level of expectation, what do they think is a reasonable amount of volunteer time to be spent on them, what do they think the response time should be, what level of research do they expect a volunteer to do on their behalf ...well it seems to me from the reports of many that often the general public have no idea how to liaise with a volunteer, for one you don’t abuse them if they don’t get back to you on that business day, hell I couldn’t get a builder to get back to me at all . Secondly don’t expect someone to do what you could do yourself, for example research if you have access to the internet invest your own time in researching a breed or an event. Where volunteers are there to guide you in the right direction it is rude to expect someone to do hours of fact finding in their own time and this brings me to fee for service, just what do people value good and accurate information at. Paid consultants exist in most agricultural fields , do people value the information given freely, its an interesting concept.

If we stop generalizing and go specifically to the RBTA we have a volunteer Board and team of Species Coordinators who are highly motivated and interested in the species they represent. They have knowledge and contacts and strive to uncover breeds and their breeders. The Board has worked extensively over the last five years on establishing this structure and the operational organization. We have done the house keeping , from Accountability to accessibility we have worked to make the Trust a secure and relevant organization and always the object of Livestock Conservation is foremost. Our website has become a go to site for many whether it be to find a breed and learn about them or a breeder or producer to support. Our Facebook group has many subscribers and our newsletter 4 times a year highlights work done. For $35 you can help fund the many costs involved - none of which are wages - and much is absorbed by the volunteers such as internet and phone costs. But we have Insurance, an Internet provider/host, Tidyclubs , the printing of hard copies of the newsletter, printing of brochures and banners for events, printing of sashes to donate to shows, an annual audit (although a change in status will render this unnecessary after this year), sponsorship of events, semen storage, as you can see there is much to fund and this comes solely from memberships, although we have been extremely grateful to receive some donations for specific things by some wonderful people. Let me tell you when such a donation arrives it brings great joy to the team as we know how valuable it will be especially when utilized in the Gene Bank program.

So how do we convert users to members ...its $35 like 10c a day, that’s just the froth on the coffee. Its been suggested that people don’t need to join because they can access Facebook and the website for free, in trying to help promote breeders we waived the membership to add people to the lists hoping that by showing them some business from the page that it would be worth investing. What do people think if its all for free is there no reason to pay. To take it up a tier and do Rare Breed Meat Marketing Accreditation or Herd accreditation it takes it to a whole new level on the administrative side, programs have to be developed, producers accredited and audited, for which they need to see a concerted marketing effort to pay for the effort. In other countries that have these things there are paid staff to run them. We are walking a fine line doing the best we can with the man/woman power that we have but not burning people out by embracing every great idea we have.

We liaised with Canada last year and our issues are not unique, they are finding their problems are similar to ours,no doubt many associations around the world are finding that the new Covid normal is making it even harder to navigate. It is probably not the most appropriate saying at the moment but "if it doesn’t kill you it makes you stronger" and I hope that this year we get the membership support that I believe would justify the combined hours dedicated to the cause by our wonderful volunteers.

Photo by Emily Humphries, Shropshire Ewe and Lamb, 2020 IHBW Fimalist

Why doesn’t the RBTA Register Rare Breeds.

Blog By Katy Brown August 2021

RBTA has been getting a lot of inquiries lately to register animals, this has occurred across multiple species and seems to be the result of several circumstances. Factors include no Australian registry for the breed/species, a minority imported breed with one or two breeders, a “found” feral breed that someone wants to record and breed up, or a herd that is not registered and someone wants us to register it as it falls outside the guidelines of the breed society – the animals may be pure but normal registration and breed society membership have not occurred. We also get asked to register recreated breeds that people want to try and reintroduce and commercialize or show. So obviously a market for registration exists but the Board of the RBTA continue to debate if that is something that we can do.

The first factor to consider is that many species and breeds already have breed societies either in their country of origin or daughter societies in Australia, others may have Breed societies and registries that are not formally recognized by the country-of-origin registrar but are a recognized Australian registry. Other breeds may have multiple registering bodies, often the result of a falling out between committee members creating breakaway groups and in some cases animals particularly horses may qualify for multiple registration. Unfortunately, animals of the same breed may be registered in different associations that do not have reciprocal rights, so progeny resulting from a mating may find themselves unacceptable by either or only eligible as a part bred. This does little for conservation and essentially dissipates the gene pool.

Breed registries should be created and maintained for the integrity and conservation of the livestock they represent. To achieve this integrity a strong committee and clear rules are necessary. Like all committees they are bound by rules and regulations and in the case of livestock are usually manned by passionate volunteers. Historically many breed societies were founded by the original importers of breeds who wanted to provide credible breeding records, pedigrees, and birth recordings for animals. To guide breeders “Standards of Excellence” are drawn up and many breeders adhere strongly to these , others unfortunately have allowed show-ring fads to influence selection criteria and unfortunately we tend to see deviations from original standards as people strive to modernize their breed to suit the judges, as breeders of heritage animals it is important that we adhere strictly to the old standards as we do not have the extensive gene pools to create new types and by selecting for a small number of traits we risk losing other traits which are often the very things that make old breeds unique.

So there begs a question … a breed makes its way around the world, becomes rare in its country of origin, and finds itself in a dubious position. In the absence of Daughter societies which are sanctioned and ruled as per the mother society in the country of origin the breed societies which spring up may or may not follow the same rules. In many cases this has led to breeds being infused with other breeds to “improve them” or to make them more acceptable to the local market. In the instance of meat breeds this may have to do with local carcass composition preference, or adaptation to local climate and feed. If the breed is governed by a tight controlling body with vested commercial interest things can go two ways, they create legislation to keep the breed pure even to the point of controlling its marketing and distribution or they bow to commercial pressures and the need to sell entires or semen and therefor are bound to create a composite registry. It is always quicker to build numbers using males as obviously they can sire many progeny and most societies see this as a commercial alternative, more registrations mean more money and more members. To use another breed is totally illegal in some societies i.e., Fjord horses and pedigree dogs, but is acceptable in grading up programs in other societies or is in fact part of the marketing policy of breeds that are renowned for terminal sires.

So for example we could have a breed that has been exported around the world , the mother society does not regulate the International registry and Standard of Excellence and over time animals of the same breed may actually start to become quite different, this can due to the influence of climate , usually cold climate breeds moved to hot climates will lose bone and get taller over generations ,but more worryingly some countries allow the infusion of other breeds then a return to the pure section of the herd book in as little as 3 generations , this is where it can all fall apart , these essentially crossbreds will show some hybrid vigor, they may grow quicker have more weight, have better fertility, on paper their EBVs may be better so of course the country sticking with the traditional lines looks at this and thinks gee we had better import some semen or a bull ,look at the figures ….the trouble is at that point the import infiltrates the national herd and effectively erodes the pure gene pool. This is the single greatest reason for uniform international breed rules in my opinion, it is usually new breeders that are most likely to fall for this mistake. Essentially is one is looking to import it should be done from a country that doesn’t allow infusions to come back into the main section of the herd book otherwise the quickest way to ruin your breeding program is to introduce an animal that may not breed true.

I digress, the first thing a registry should do is provide a transparent birth and pedigree record of the population including all the original Imports and AI, if the registry is run as a daughter society the rules will apply as per the country of origin, ultimately purity should be fully traceable via extended pedigrees and because of exclusion of other breeds via grading up or cross breeding.

Grading up is usually the result of minority populations existing in a country where the female population is limited. If a grading up program exists, then transparency should be recognizable by different herd book prefix numbers or sections in the herd book. Grading up is usually a 5-generation project using a purebred male over a female of another breed, preferably pure so prepotency can be expected, the first cross at 50% is generally called Foundation Section ,50% x 100% FS1, FS1x 100% =FS2, FS2 x 100% = Australian upgrade Australian Upgrade x 100% may or may not be accepted back into the herd book as a “pure bred”, some registries have less generations. The key to success in any upgrading program is the selection of a suitable foundation type for crossing with ,one needs to be mindful that in the absence of a good similar type foundation cross it will take much longer to secure the type and get back to the true standard of excellence, breeding out the unwanted traits is a lot harder if the original cross has traits not accepted by the studbook i.e. white markings ,lop ears etc. This type of breeding, sometimes done to reinvigorate commercial viability into an old dairy herd by using them as a foundation for a beef or dual-purpose breed often leads to a split in types within the herd book. Good selection is critical in these circumstances and inferior animals that don’t meet the standard ideally would be culled rather than registered. Culling of animals that have meat value is easier than in species such as horses which tend to be registered regardless. Some registries combine registration with classification where the animal is presented to an expert panel prior to acceptance. This has pros and cons and unfortunately rejected animals may cause reasons for splits in committees and groups and hence we see breakaway groups formed. Interestingly in Canada it is legislated that only 1 parent body may act as a registry.

In my long association with several breed societies, I have observed that the most successful bodies have both Federal and State Committees manned by committed and enthusiastic members who are working for their breed -not for their own interest. They have sub committees to do things like run events, run websites, edit newsletters and journals, they are well balanced with old and young breeders/members, and they have junior committees to train up new people. It is the combined knowledge and commitment to the breed that ensures correct registration procedures are outlined and followed. For example you may have to submit breeding returns at the end of the breeding season so the society has a record of mating’s, then as a baby the progeny may be recorded to be upgraded to full registration by 4yo sometimes with veterinary inspection or Classification ,a record of markings ,whorls ,brands, accompany the paperwork so the animal can be visually identified, many breed societies also require DNA testing for parental validation (this works when all animals in the registry are DNA tested).

So, what would be the biggest hurdles to the RBTA simply registering animals, gosh I can think of quite a few the least of which is that we are a volunteer organization focusing on many species funded purely by membership and many very financial breed societies subcontract the registration part of their organization out to businesses set up to do this task for a fee which is recouped as part of the registration fee. It follows that the creation of a registration entry needs for it to be viewed online or in an annually printed studbook, this is usually the task of the registrar, so it is not as simple as printing out a certificate based on what the applicant said. This information also needs to be checked to ensure it is correct and viable, this requires cross-referencing with other documents like breeding returns and animal transfers or leases. Essentially no one should be able to register an animal except its breeder or a person acting on their behalf.

The registrar needs to be backed by a strict set of guidelines to which members of the association applying to register an animal are aware of and adhere to, a breed society to create the Standard of Excellence, the Rules and Regulations, the recognition of members and their stud prefixes, brands, tattoos etc. This is not a simple thing and groups find they may need to become Incorporated, have Insurance, have financial audits, have AGMs, have a committee, keep minutes, have a public face via a website or Facebook page, have a social media policy, ultimately there is a lot more to a breed society than the issuing of a certificate.

Ultimately without a good Breed Society, a strong committee and a stringent registration and traceability process, to issue a registration certificate issued based on information submitted by an individual with no checks and balances would erode the integrity of the process and it would need a great deal of work to set up a system that offered the same intellectual, historical, and passionate breed society knowledge and governance.

At this time RBTA can help provide guidelines as to what would be accepted as a breed (there is an international guideline for this) and help direct people towards Breed Societies and breeders to source purebred livestock.

Have You Thought About What Happens to Your Livestock

When You are No Longer There To Care ForThem

By Katy Brown, RBTA Secretary

Here are some thought provoking comments which are very relevant to what is going on in our lives and community at present.

People have often said to me that I was in the right place at the right time. They are referring to my

Tamworth herd and how I became the successor of several studs as they closed down their

tamworth breeding herds. These included Green Gables, Kings Flat , Spring Hill , Jurumbula and a

few others. Had I not been there at that point in time these animals were often on their way to the

abattoir and the end of a life’s work, whether it was luck or destiny I can never quite fathom. The

thing was there was succession, I was a registered breeder and have continued on for 20 years.

However over the last five years many have left the pig industry ,many new rules have come in

making it harder to farm pigs and in general people are moving away from Breed societies and

registration deeming it irrelevant to their operation usually citing cost or the fact they only want to

produce meat. This does not bode well for rare breeds particularly those that require niche

marketing.

So on farm I have implemented some important strategies should I drop dead tomorrow , some are

works underway and some are complete but I have seen the Covid crisis as a wake up call to get all

our records and paperwork in order so should I disappear its all there for someone , hopefully , to

then ensure my work is not lost and the breeds can go on to the future.

Basically the plan looks like this:

1. Identify all livestock on farm without delay using the relevant ID whether that is Brands ,Ear

notches, tags, microchips etc and maintain a list identifying the number to the paperwork ,

remember if an outsider came in they have to match them up. (note this is normal practice

but can fall behind).

2. Ensure that all recordings and registrations are up to date.

3. Ensure Society memberships are paid should someone have to transfer.

4. Let some common minded people know where treasures such as herd books, photos and

records are stored. Digitize as many as possible and store on a Memory stick.

5. Identify any last of line animals for utmost importance ie red tag so without any other effort

someone could see which were the most critical to preserve.

6. Increase replacement matings to ensure numbers of each line, cull less so more animals are

available for distribution to other breeders. This is important and requires serious

investment and commitment. With ASF threatening our industry this is of utmost

importance.

7. Archive the record with RBTA (not for public view) just incase RBTA had to step in to secure

the livestock

8. Nominate other breeders you would be happy to pass the animals onto, discuss this with

them and make sure their breeding and conservation philosophy is sound.

9. Ideally via mentorship ensure a network of likeminded breeders that recognize the genetic

value of the herd.

10. Wear a mask.

I asked the solicitor regarding wills the animals are in the will but without the relevant ID registration

and records they will not be of use to a true conservation breeder.

2019 Rare Breeds Trust of Australia Poultry Survey

by Cathy Newton

A few months ago I was contacted by the RBTA and asked to run their online poultry survey. I set about constructing the survey using the Australian Poultry Standards as the basis for the breeds to be listed. Melissa Gollin, who ran the 2017 survey, was consulted and her feedback influenced the following changes that were made. The requirement to give a postcode to indicate location was removed as many poultry breeders will not participate if their location data is collected; an optional residential State was offered; and standard and bantam were split in the data. The survey ran for a month to match the previous collection. Many poultry clubs and contacts were emailed details of the survey, asking them to forward it along. It was advertised widely on Facebook and other online locations. A paper copy, or the opportunity to submit email data was offered to anybody who enquired about those options, but nobody took up those opportunities. The survey was run online as that was the most efficient and affordable way to collect information. There is no reason to believe that this bias to online participants is correlated to any bias in breeds. The breed data collected should be a fair sample of the wider population.

We recognise that the poultry community would like to see colour varieties represented in the survey. We considered this for the 2019 data collection, however it would have become too large and unwieldy. It was decided that we consider sectional surveys at a future time in order to cover any pertinent colour variety information in surveys of a manageable size. The survey stated that birds entered must be of breeding age and be a standard breed. No quality information can be deduced from this anonymous survey.

In the past this has been called a census but it is more accurately described as a survey. A census implies that every possible poultry owner is included, but the reality is that is not achievable. This survey endeavoured to reach as many poultry keepers as possible given our resources and gives us a good idea of what breeds may be at risk in this country.

Poultry is eligible to be included on the RBTA Poultry Red List if their status is regarded as being Critical, Endangered, Vulnerable or At Risk. Special priority is now also given to those breeds that have been on the Red List but have shown recent increase in numbers. These breeds are given an Amber status to reflect the need to watch and maintain support as there can be reasons for transient alterations in numbers.

Poultry is eligible to be included on the RBTA Poultry Red List if their status is regarded as being Critical, Endangered, Vulnerable or At Risk. Special priority is now also given to those breeds that have been on the Red List but have shown recent increase in numbers. These breeds are given an Amber status to reflect the need to watch and maintain support as there can be reasons for transient alterations in numbers.

Results

2012 respondents completed the 2019 Survey and 77,420 birds were accounted for in the responses from participants across Australia. The survey attracted approximately two and a half times as many respondents as the 2017 data collection. The respondents were spread across the wider poultry community including both the exhibition community and the rare breed community. Respondents also came from all States and Territories of Australia. This large sample has given us reasonably reliable data from which to draw some conclusions.

Poultry numbers had generally increased. Twenty poultry breeds moved from the Red List to the Amber List (Recovering) as a result of returning more than 500 adult breeders in the survey. There may be a number of reasons for this and their new status in the Amber List recognises that they need to be watched into the future.

Of the twenty-one poultry breeds remaining on the RBTA Red List, three are critically endangered. These are the Sultan, the Yokohama and the Old English Pheasant Fowl. The Sultan and Yokohama have never been seen in big numbers in Australia to my knowledge but they do exist and are held in the hands of a few breeders. The Old English Pheasant Fowl is an Avgen import that has only been here a short time. Some of the imported breeds have taken off and become popular quickly but the Old English Pheasant Fowl has not done that at this stage.

What cannot be seen in the list below is the split between bantam and large as the RBTA List deals with breeds as a whole. We did split the data in the survey and the results tells us that a number of large or bantam may be at risk. Examples are: Large Modern Game (98 in the hands of 12 breeders); Bantam Minorca (81 in the hands of 10 breeders); Bantam Malay (113 in the hands of 12 breeders) Legbar Bantams (16 in the hands of 3 breeders); Faverolles Bantams (116 in the hands of 13 breeders); Dorking Bantams (45 in the hands of 5 breeders) Croad Langshan Bantams (13 in the hands of 2 breeders); Bantam Barnevelders (78 in the hands of 8 breeders); Araucana (224 in the hands of 42 breeders) and Andalusian Bantams (70 in the hands of six breeders). Some of these breeds are no longer on the Red or the Amber lists however are at risk in terms of their variety rather than their breed.

Poultry breeder numbers were strong. Among the respondents we had an average of 88 breeders per poultry breed, with over 20 breeds having breeder numbers of more than a hundred.

The waterfowl did not perform as strongly as the poultry and may be in need of even more support. Just two breeds were moved from the Red List to the Amber List despite increased survey returns. These were the Australian Call and the Indian Runner. The Australian Call in particular has made strong growth from 402 in 2017 to 1366 in 2019. This increase is reflected in the numbers of Australian Calls seen at shows around the country. Indian Runners have always been a popular breed due to their strong egg laying capacity and also their potential as a show bird. They moved from 493 in 2017 to 1201 in 2019. In recent years Runners have been seen in a wider varieties of colours and this may have contributed to their growth as a breed.

There are twenty-nine waterfowl breeds remaining on the RBTA Red List. This includes nine on the Critically Endangered List, however one of them, the Pommern, may not be in Australia. It was included in the survey as it is in the Australian Poultry Standards. The remaining eight waterfowl breeds in the Critically Endangered List are: Abacot Ranger, African Goose, Bali, Pomeranian Geese, Brecon Buff, Magpie Duck, Rouen Clair, and the Watervale.

Geese performed poorly within the waterfowl section. Most of them fell in the lower parts of the Red List. This may be due to the difficulties of keeping geese in urban and even semi-rural areas these days. The strongest goose breed was the Chinese with 324.

Breeder numbers are big factor to consider in the status of breeds and across the entire waterfowl spectrum breeder numbers are consistently low compared to poultry with an average of 24 per breed compared to 88 in poultry. No waterfowl breeds had a hundred or more breeders. The number of waterfowl respondents represented around 13% of the total. This result shows that these species are at-risk to a greater degree.

Overall waterfowl should be a huge priority for conservation and it would be good to see efforts made to promote them in a variety of ways.

Turkeys and Guineafowl were two species where colour varieties were represented in the data. This was an experiment to see how that worked. We had mixed results as people entered numbers that didn’t add up to their totals and we could see that accuracy of the data was in doubt. We chose to work with the given totals rather than the smaller broken up colour variety numbers.

In Turkeys we can still follow some trends in the data. The biggest numbers were in Bronze and in White, with solid numbers in Royal Palm, Naragansett, Slate and Bourbon Red. There were quite low numbers of Blacks, Blues and Buffs which all had numbers less than one hundred. We also noticed that in Turkeys, the numbers put them outside of the Red List, however a large percentage of the turkeys were owned by one breeder in South Australia who entered 2000 birds. Overall there were 60 turkey breeders with most having smaller numbers. Without the single bigger breeder, turkeys would return to the Red List.

Guineafowl numbers were greatest in Pearl and Pied, closely followed by Lavender. Cinnamon were less common and five breeders claimed to have small numbers of white guineafowl. As a species, Guineafowl are not on the Rare Breeds List.

In summary, in this survey poultry appears to have strengthened but waterfowl has shown up as a big area of need. The next survey is expected to take place in 2021 and recommendations for improving the survey are already being recorded and noted for that event.

For more information about the 2019 Rare Breeds Trust of Australia Poultry Survey, please visit http://rarebreedstrust.com.au/public/pages/poultry

Work in progress

By Tessa van der Linde

The first evening I spent with Judy and Richie from Tilba Tilba Farm where I was going to stay for the next couple of months was a true adventure. When I got out of the bus the friendly couple came to pick me up, but we were not yet to drive to the farm as I had expected; instead, we drove an hour to Warwick, because Judy and Richie wanted to sell 3 pigs (2 Tamworth and Wessex Saddleback) and 2 Roosters (A Golden Campine and a Barnevalder) at the Warwick Pig and Calf sale. The sale would only happen on the next day, but this was the best time for them to get the animals there.

When we arrived however, it was not only dark, but we also realized that they had forgotten the pig boards they normally use for the sides of the ramp to unload the pigs. So we did a little improvising and tried to use some old wooden doors as a replacement/to replace them. Well, as we found out, one of them was broken, but we managed to get the pigs in their pens somehow anyway. (We were later disappointed to learn that they were sold for only 150$ each – these pigs were a rarity!)

So now, after this mission was accomplished we were to drive 2 hours to my new home with only a stop at McDonalds to get our stomachs filled. And a second stop at the gas station to change seats, so that I could sit in the front and spot some wildlife.

And I did. There where loads and loads of Kangaroos and Wallabies on the way here. I’ve only seen two Kangaroos in the wild before – one of them I only spotted on the same day – but here they were; sometimes only one, but from time to time we saw about 8 in a mob.

A truly thrilling experience, I can tell.

It took us an hour or so to get to the farm, but finally the front gate showed up. Then, at the second gate, I saw the first sheep. Dorset Downs and Southdowns - I could tell the difference, because I learned about them on the farm’s website. They were lying in the grass trying to sleep; we had awoken them as it was already 11pm.

We finally stopped the car at a lovely house. As soon as we got out, we heard it: “Baa!”

Turned out, the three little lambs Edward, Jaz and Tiny Tim (which were fed by hand) had gotten their way out of their paddock and were waiting for us at the house. They hadn’t been fed yet as Judy didn’t have the time to do that, so they probably felt like they were starving. Judy took them into the house and prepared some milk for them.

I have not often seen something that cute and funny at the same time. Lambs look really cute (okay, I admit, when you look a little closer, some of them, like Tiny Tim for example, look like they are grandpas), but their tail goes crazy when they drink milk. It looks like they would suffer from a twitching disorder (????). Have you seen a dog who is really happy and their tail goes from left to right and back really fast? Yeah, nothing compared to that.

Anyways, we went to bed around midnight, which only left us about five and a half hours to sleep. Because as a farmer, who also has to manage a regular 9-5 job, you have to do all the feeding very early in the day. Also, it’s not too hot yet (it actually was freezing the next morning), which is very, very nice.

So, the next day was my actual first day on the farm. I will not write about the details, because it would simply take too long, but let me give you some general information: The animals we have to feed daily are different kinds of chocks - and chickens! – (they go nuts very fast when you try to approach them and they sound very funny when the discover the new food you just gave them), shorthorn cows ( these animals have such cute noses – and are apparently the only ones who are at least a little calm when it comes to feeding), goats (horns; do I even have to write about the pain you will suffer if you let them wait for their food too long?) and finally sheep (you don’t even have to let them wait too long, as soon as you arrive with a bucket of food in your hand, there will be sheep 360 degrees around you – they would totally knock you over if there weren’t sheep on the other side to push against you). Dogs, Smokey the cat and a bunch of guinea fowls (to keep the snakes away; just entertaining when they run after each other and fight) not included.

There’s a lot to do here every day. And the drought makes it worse. Judy and Richie have told me that there actually was a river on this land but you wouldn’t know the first time you’re here. There’s only a bridge left.

We really hope that there will be rain soon. Until then, we’ll just have to wait and drink tea. A lot of tea.

Note: Tessa is from Germany, she is 19 years old and dedicated to her work on the farm! When she returns to Germany she goes into Uni to study Environmental Science.

colour sided cattle pattern

Some breeds are uniformly marked with the colour-side pattern. There are two distinct types of the colour-side pattern.

Lineback has clearly defined markings of solid colour, and white. Solid colour heads. Lineback pattern is beautifully demonstrated in Pinzgauer and Gloucester cattle.

Photo is a Pinzgauer, Ivan Dunley's cow Lena.

Witrik has roaning, speckles, big spots that may be elliptical or round, and varying degrees of white.

In this pattern , the ears, nose and ears are pigmented.

, the ears, nose and ears are pigmented.

White is seen on the heads of witrik cattle; think of English Longhorns. The head white may be anything from a little roaning on colour, to pure white. There is white on the back.

There is a pattern called "white faced colour side" which covers Hereford and individual animals from other breeds such as Montbeliards that sometimes have a colour sided pattern - but also lack nose pigment. They retain the ear pigment and sometimes around the eyes, just like Herefords.

Some breeds are 100% of the colour-side pattern; with some, such as Riggit Galloways, the pattern varies considerably within the breed.

In other breeds of varied coat patterns , the colour-sided pattern appears randomly, proving genetic diversity allows patterns that may otherwise have been lost, to remain within a breed. It is quite dominant so can be kept in a line if wanted.

Lineback has solid colour; being red, through to dark brown, brindle, or black, and rarely, blue; with white tail switch, white rear end, white topline and white bellies with the white usually crossing the top of the legs in Pinzgauers. Head is solid colour. Legs solid colour.

The purpose of the ancient patterns are to break up an animal’s outline, so it was better camouflaged. It’s also found in yaks. Witrik is seen in several breeds. The speckles are called brockling or finching in different geograpical areas.

Photo: Telemark cattle, Norway, from Nordgen website.

Photo: Telemark cattle, Norway, from Nordgen website.

Some people do not use the terms 'line-back' or 'witrik' - but simply 'colour-sided'. It does save confusion! - as it would appear none of the terms have concrete definitions.

Herefords have white faces with the white topline incomplete; lower leg usually white; a witrik pattern. The white top line of Herefords is abbreviated, being white from head to over the shoulders and coloured from there on. The face and most of the head is white without roaning - almost always with lack of pigment of nose and eyes. A few breeders are keeping the eyes pigmented, this helps pevent pinkeye, sunburn and weak eyesight. Although some noses may be speckled or coloured, it has always been looked on as a fault in Herefords to have "a dirty nose" - fashion plays a part in these ideas too. Some Simmentals, Montbeliards and other breeds have the white head witrik pattern without roan or pigmentation of nose.

Photo Richard Gunners English Longhorns.

The witrik and lineback patterns occur in several breeds - including English Longhorn, Texas Longhorn, Ayrshire, Belgium Swiss, Shetland, Simmental, Maine Anjou, Lithuanian White Back, Black Sided Troender, Normande, Welsh Lineback, Telemark, Galloway, Meuse Rhine Yssel, Dutch Friesian and Irish Moiled, Lynch Lineback and Randall Lineback.

Witrick has been identified in three variations - White Witrick, Dark-Sided Witrick and Dark Speckled Witrick – in the latter the sides are not solid colour, but speckled, also called brockled and finched, including bigger elliptical or round spots

Nguni are a sanga breed from Africa. Colours vary but some have the witrik pattern. Of interest there is also a reverse of it, where the outline is coloured, and body is white with speckles. The crossing of Pinzgauer with Nguni and Nkone in Africa means the pattern may have been introduced via Bos taurus; this is but conjecture.

Dutch Friesians have the pattern in the breed. This line is sometimes called ‘the Witrik Dairy Breed.’ In fact it’s a colour line within the Friesian breed. In the Netherlands and America it’s bred for and who knows may be regarded as a separate breed at some stage.

A few Gyr seem to have a variation of the witrik pattern - darker accents to the top, tail and legs, speckled sides. Ears, nose and eyes are pigmented, in keeping with colour sided patterns. Some have a pattern wi th colour, not white, along the back, back end and legs. If the pattern can be tested for, they may be found not to have it at all. Not sure if tests are possible.

th colour, not white, along the back, back end and legs. If the pattern can be tested for, they may be found not to have it at all. Not sure if tests are possible.

Photo : Texas Longhorn 'Concealed Weapon' from the Singing Coyote Ranch.

To my knowledge the colour side pattern is specific to some breeds - occurring in all animals of that breed - only in Bos taurus cattle being UK, Irish and European breeds. However it is seen, mostly as the witrik version (light face, roaning and speckles) but also lineback (solid colour face) in Bos taurus, Sanga, and Bos indicus (zebu) in individual animals. Historical photos, paintings and documents would be the best way to discover if the pattern was in certain breeds. I have found no zebu or sanga breed that is entirely colour sided (although there may be some, would would like to be enlightened).

Photo :Pustertaler Sprinz en, from Wiki, an Austrian breed

en, from Wiki, an Austrian breed

Several studies have been conducted into the DNA of these colour patterns.

The pattern is caused by DNA fragments moving from one chromosome to another in a circle. If two fragments go to the same chromosome, the animal will have a lot of white in its coat. These chromosomes have been identified (see reference).

In some breeds a few breeders have strived to keep animals of the colour sided pattern – it traditionally occurs in many breeds. Breeds such as the Galloway, the Dutch-Friesian, Belgium Swiss and the Meuse Rhine Yssel have dedicated breeders, although in a minority, maintaining the colour side pattern in their breed.

Photo - Riggit Galloways, fr om the Riggit Galloway Cattle Society.

om the Riggit Galloway Cattle Society.

Riggit is the Galloway breed term for the colour side pattern. Of interest, there are photos online of Riggit Galloways showing the otherLineback pattern (witrik), with solid coloured heads, clean white backline and back end, with no roaning or spots.

Reference for DNA mentions: New Genetic Phenomena discovered in Witrik Cattle. Waginen University, Netherlands, originally published in Nature magazine. Extract of article at below website. https://phys.org/news/2012-02-genetic-phenomenon-witrik-cattle.html

Janet Lane RBTA 2019

CONSERVATION LIST HIGHLIGHTS SHEEP 2019

The Good News.

The Lincolns have increased slightly in number going from 252 to 295 registered breeding ewes, which makes them only five shy of moving from Critical to Endangered.

The Persian numbers have increased from 249 last year to 377 this year, moving them from Critical to Endangered. We have also heard from Dr. Colin Walker that Coolibah Persian Stud is now exporting Persians overseas, which is a tremendous effort and to be applauded.

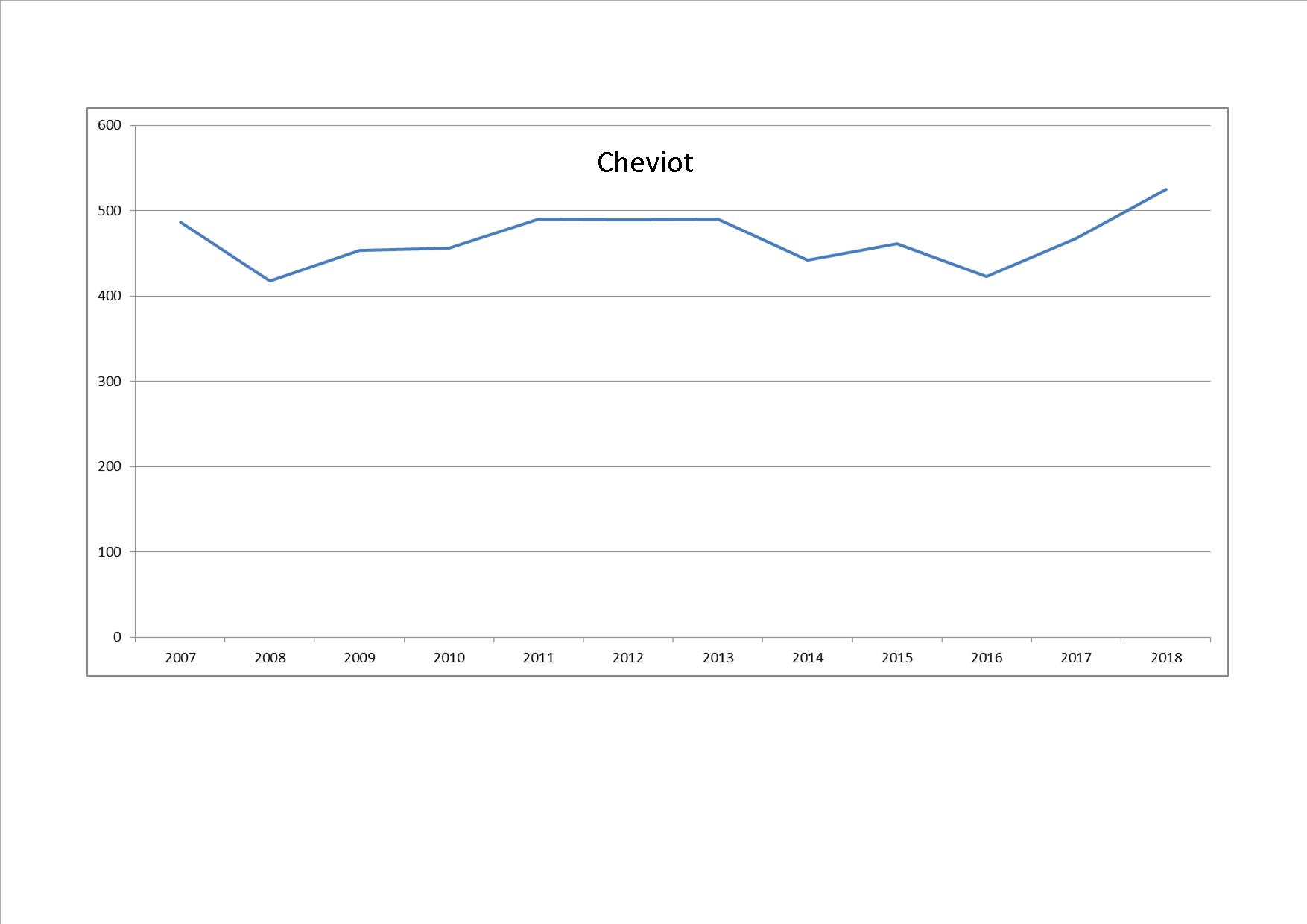

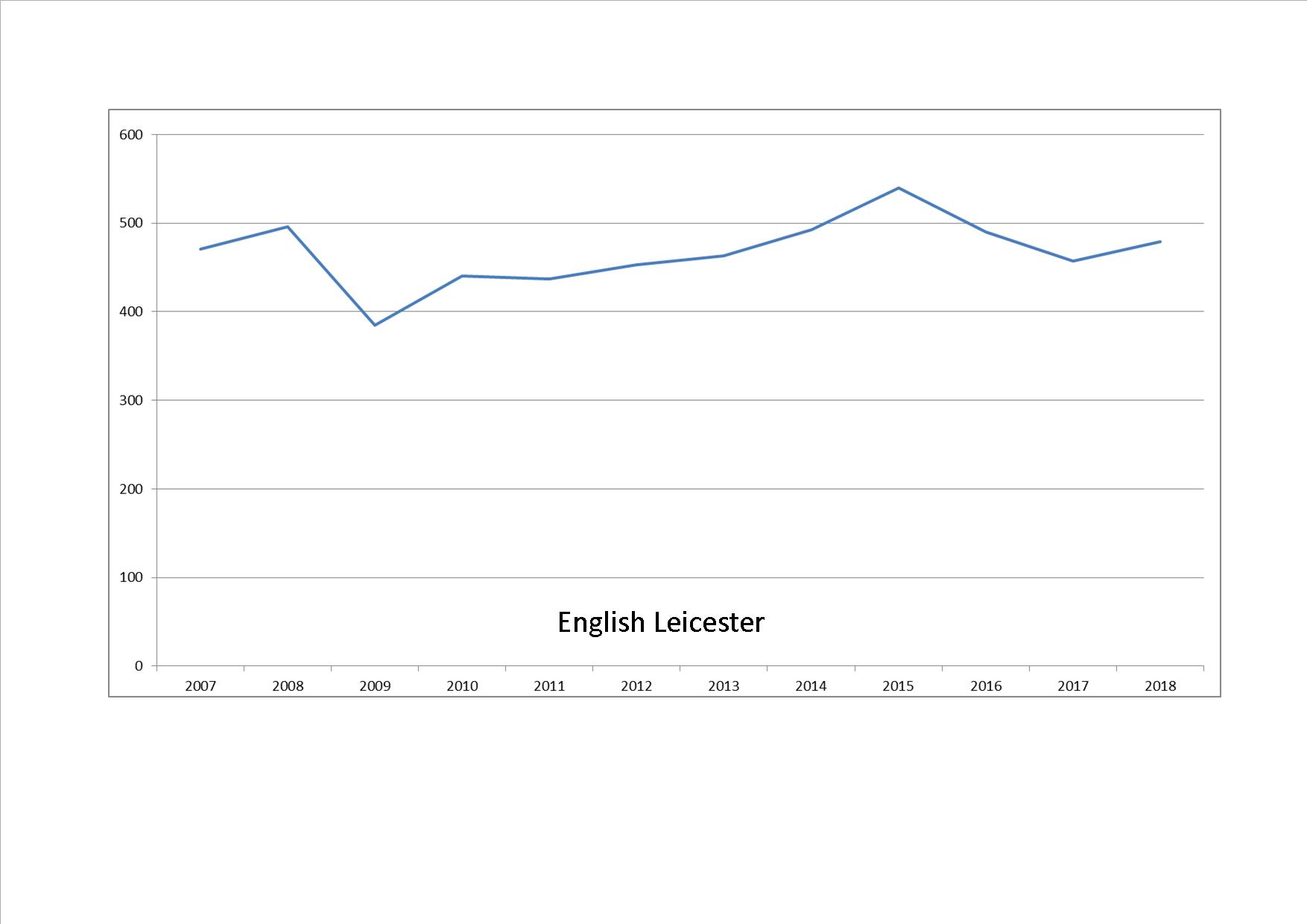

We have great news from all of the breeds in the Endangered category, with two of the breeds moving from Endangered into Vulnerable. The Cheviots have increased from 467 registered breeding ewes to 525 and the Perendales have increased from 493 to 586. Great work to all the breeders of those two breeds. The English Leicesters have increased from 457 to 479 and the Shropshires from 308 to 452, with the re-registering of an old flock, which is great news. Congratulations Shropshire breeders!

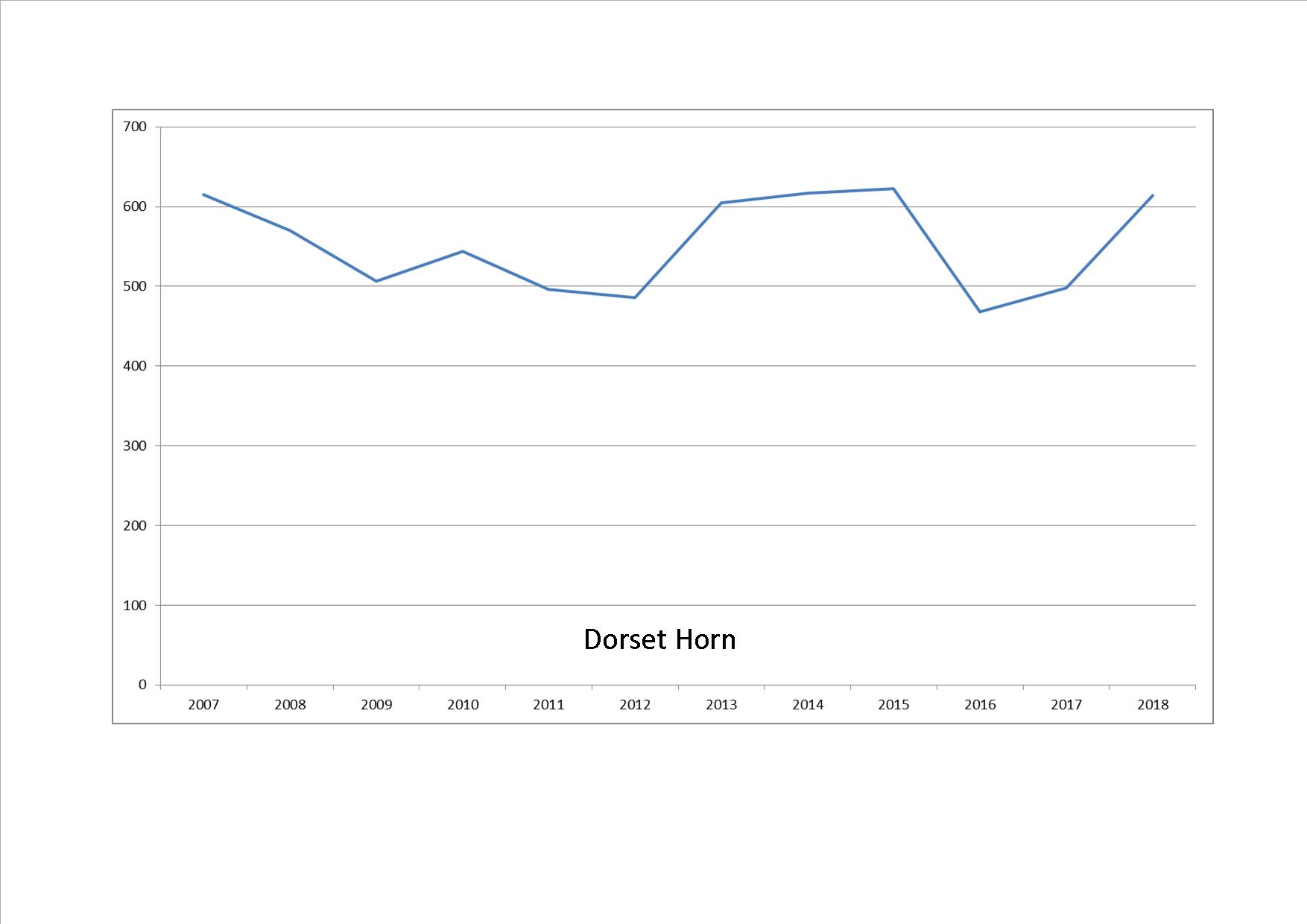

The Dorset Horn breed has had another really good increase going from 498 registered breeding ewes to 614, with four new flocks on the scene.

The Not So Good News

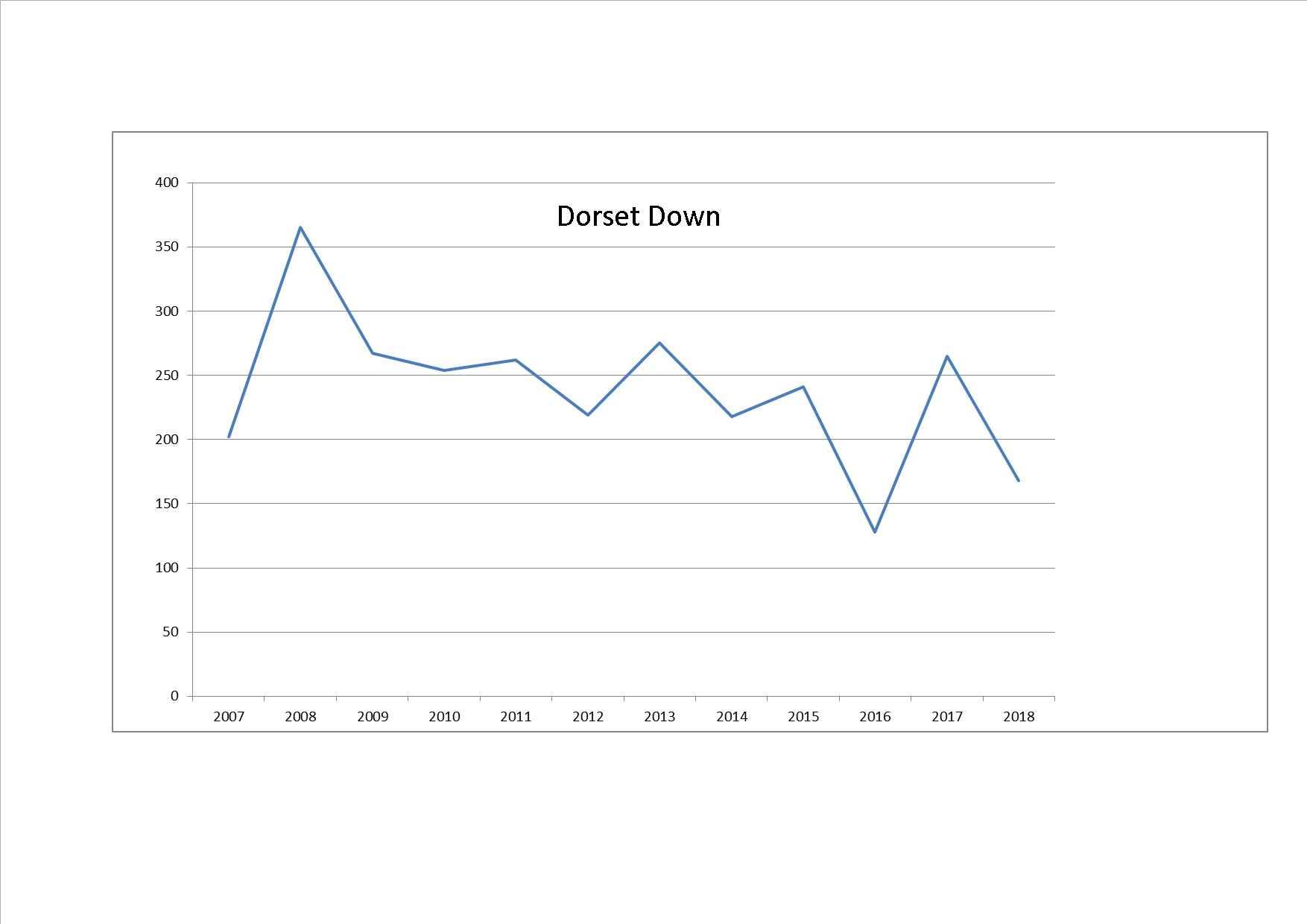

The Dorset Down breed is at it’s lowest number in the last ten years with only 168 registered breeding ewes, down from 268 last year, so this is a breed that needs our help.

The Romneys have also had a slight fall in ewe numbers number which is not great as they seem to be decreasing slightly each year. But they have seen an increase in actual flock numbers, so that is good news.

The East Friesians and the Ryelands do not look good on paper with the East Friesians dropping from 510 to 249. I suspect some of this is due to breeders not getting their annual returns in on time. Likewise with the Ryelands, where the number has dropped from 583 to 332 registered breeding ewes. Again some of this will be breeders missing the deadline. The South Suffolk have been slowly decreasing each year since 2010.

Finnsheep have also been added to the Watch List, with Damaras about to be added, both will be in the Critical category.

The Carpet Wool Breeds

The three carpet wool breeds have managed to stay around the same in number but all three require new breeders to become involved, particularly the Drysdales with Wendy Beer still having the only flock. These three breeds are to my mind the flocks most at risk, as Australia is the only country with Elliottdales and Tukidales and New Zealand does not appear to have many Drysdale flocks left either, to the point where they are no longer being counted and a flock is being taken on by the Rare Breeds Conservation Society as a safeguard against extinction.

Graphs of Registered Ewe Numbers over the Past Twelve Years

THE STATE OF THE PIG INDUSTRY

THE STATE OF THE PIG INDUSTRY

By Katy Brown, The Accidental Pig Farmer

(Photo, Saddleback Sow, Photo by Corina Till, IHBW 2017)

In my role as Pig Species Coordinator, I have seen one of the toughest 18 months our industry has ever faced with many producers leaving the industry. Many farms have been losing up to $30 a head on the Cost of Production (COP) and pig prices have been as low as 17c a kg. In some case, pigs haven’t even found buyers in public markets. The current price is up 30c a kg but still far too low. The flow on effect this is having on rare breed meat sales has seen 14 Berkshire breeders from Vic, NSW and SA close their doors.

This has left quite a hole in the market and the few still producing have been lucky to find ready-made markets. Many smallholders with a handful of rare breed pigs are finding that the combination of drought, high feed prices and issues getting domestic pigs slaughtered and to market is just too hard and we have seen several small herds either disperse to other breeders or go for meat. Like many minority breeds, the old breeds such as Large Black, Wessex Saddleback and Tamworth are very much suited to smallholdings and this is definitely having an effect on these breeds. Many Wessex have disappeared over the last two years as people have lost abattoirs or markets. I fear greatly for all the pure breeds but particularly the Tamworth, at present two of the five long-term breeders are on the verge of quitting.

This year we have had a focus on Large Blacks and have done some really good work introducing breeders and providing mentoring and support for newcomers. The inception of the Pedigree Pigs Australia Facebook site, moderated by Christine Ross from Eastwind Rare Breeds Farm has really become a “go-to” site to communicate quickly with other purebred breeders. It is due to this site that we have “saved” three registered Tamworth’s and over a dozen large blacks from around Australia. Currently, I feel more confident about the safety of the Large Black breed than in many years.

The pig Industry and therefore our Rare Breed Pig Studs are all facing several pressures which will see a lot more leave the industry in the next 18 months. Fast communication via social media hopefully will mean that we will be aware of animals that may be going for slaughter so we may step in and rehome them. Unfortunately, it is usually a “straw that broke the camel’s back” situation that sees livestock on a truck to the abattoirs and you often don’t find out till too late, more than one rare breed line has been saved from a kill pen. Just last week we “saved” some Black Jack boars, the last of their line from the meatworks.

The Pig industry is facing some major challenges that have been active for at least 18 months.

These include but are not limited to;

* 7% increase in production leading to domestic oversupply

* Supposed a 13% drop in imports over this period so the government does not acknowledge that importation of no tariff Pigmeat is hurting domestic trade.

* $88 million worth of ribs and bellies are coming in under a loophole this cooked two-year shelf life product has had an impact.

* Closure of several domestic abattoirs including four in Victoria, one in Tasmania and as of yesterday another in South Australia.

There have also been at least three abattoir fires which have seen partial or total shut down for rebuilding. This interruption or cessation of a critical link in the supply chain all makes the supply of pigs to the domestic market a challenge, limited places to kill and limited delivery routes mean many cannot service markets they could have.

Continued over regulation regarding meat sales have been somewhat lightened as there is a suggestion that farmers may be able to sell on-farm from their farmers market trailers, in Victoria Primesafe continue to make life hard for all sectors and poses ongoing hurdles and costs for small producers. Next year will see the beginning of a new project with the start of The Barham Micro Abattoir Co-operative with which I am affiliated, this model may be one of the ways forward for Rare Breeds giving owners control of the Slaughter process.

This year I wrote two very long submissions to The Planning for Sustainable Animal Industries code which will provide legislation on livestock keeping. Although some herald this as a positive thing for very small holders it is not a good thing for medium density farms. I believe it is just another nail in the coffin to medium-sized livestock production. Basically, to supply a market you need enough production to be viable. Livestock suited to small farms face limitations under this code that are not positive for stud herds as opposed to commercial herds. In all the discussion those in charge had no real knowledge of farming practice or pure stud breeding. To be honest, I am not sure how some of these people end up as decision makers in these processes. More red tape, regulations and paperwork for farmers which all makes our job of preserving rare livestock more challenging.

Going forward into 2019 I am anticipating huge challenges on my own farm, in the last 12 months, we have had just over 200mm of rain, lots of days over 35 and hot north winds almost daily. This has affected our production via summer infertility and has created the ongoing issues with feed, both pricing and availability. I have been waiting three extra days for an order of ten tonnes. They rang this morning as said I can get five only, this is due to grain shortage and rationing between all clients. Not a lot of grain is being harvested locally, it’s all gone into hay, and that hay is going straight off-farm at $150 a bale to the desperate dairy farmers. By winter I am predicting hay and therefor chaff will be either not available or so expensive it isn’t viable. Grain at harvest will be over $400 per tonne. On the current pig meat prices that means it is too expensive to feed to pigs, at about $170 - $190 it’s viable. This poses a huge challenge and whilst we think the drought is affecting us now wait till before harvest next year we will be desperate.

This, the poor prices and the problems caused by a lack of domestic abattoirs will be massive issues for all farmers, many rare breeds farmers have other jobs and my fear is they will see their animals as too costly and offload them. For me, it is a full-time job and with one of the largest herds of rare breed pigs, it feels like a total rethink of our business model in order to ensure we survive.

I sincerely wish all my fellow rare breeders all the best in these trying times and hope sincerely we lose no breeds in the next 18 months.

25 November 2018

Foreign Ownership of Farms

Good for nothing

One of the biggest threats to rare breeds is foreign ownership of land. Australian farms are being sold off at record levels. Farming is becoming increasingly unviable with ‘free trade’ (aka slave trade) - it’s hard to compete with no or low import tariffs, and the exploitation of human labour in some countries which results in cheap produce.

Trump is waging a trade war. If some countries suddenly lower tariffs and others raise them due to political pressure, it’s big trouble. To be able to sell at a fair price, if a regular market suddenly puts up a huge import tariff, other markets must be urgently sought. For whole industries this is impossible to do instantly - it takes time.

The dairy industry in Australia has been so badly regulated, for so long, it’s ending multi-generational farms as they can’t make a living. The sharks are waiting - while the government encourages foreign ownership and forces our farmers off the land, sharks rush in for the kill. Drought, combined with deliberate government neglect of its duty of care, is now forcing more off the land.

Once foreign companies buy large properties or several small ones they merge together, their mantra is invariably to ‘double production’. This becomes intensive farming.

As we have recently seen with giant intensively farmed dairies in New Zealand, intensive farming always brings disease in its wake. Anything remotely contagious spreads like wildfire. Not only is mastitis, always associated with over-crowding, rising alarmingly, but other associated lethal illnesses from Mycoplasma bovis is also raging through these intensive farms. Over 100,0000 cattle slaughtered out of hand to try to combat this already, this year, and more facing the gun. A terribly cruel waste of life. Yet the practices get worse, not better, that cause it. While the number of dairy farm owners in New Zealand has halved due to amalgamation by big companies, the number of dairy cattle has doubled. That tells its own story.

Another of their sins is ignoring climate change. The giant New Zealand dairies feed PKE - palm kernel expeller – imported from south-east Asian forests which are denuding trillions of acres and wiping out species such as the orangutan. NZ is the world’s biggest user of PKW. Its industry is now called “dirty dairying.” Appropriate, as Fonterra is the dirtiest word in Australia in dairying. This foreign (NZ) company has been allowed to set up a virtual monopoly, governing milk prices in Australia. Over half the milk sold in Australia is by foreign-owned companies. The money goes out of the country. While Fonterra supports its farmers at home in New Zealand and destroys ours, the foreigners come in for the kill - New Zealanders have also been buying many Australian dairies.

Will PKE now be imported for our dairies? Yes. Disgustingly, Moon Lake – new Chinese owners – are feeding it in Australia’s biggest dairy. Foreigners want massive production at any cost. Palm oil is one of the unhealthiest products on earth, carcinogenic - sold extensively as “vegetable oil” – will PKE affect cattle and milk health too? Ironically, their milk will be marketed as organic!

Only this week Americans, through Australian firm Laguna Bay, bought at least eight family dairy farms in Tasmania – some $50 million worth – and boast of plans to double output. On top of the recent Chinese purchase of Australia’s biggest dairy - VDL Farms in Tasmania -some $280 million worth - by Moon Lake, also upping production drastically.

There is no place for horned cattle in these squashed intensive dairies with no room to move. No room for other breeds. There is a huge need for water. A huge need for antibiotics. A huge need to get rid of trees for giant irritators, a huge need for cows to give more and more, an absurd amount per day, at the expense of their health, calving ability, fertility, longevity. A huge need for occasional mass slaughter from a disease. That impacts innocent neighbours who might be farming properly – their precious stock will be slaughtered too, in big government kills to stop the disease.

There is no regard for animal welfare - in giant intensively farmed operations, animal abuse is routine. It is unavoidable. The animals have very short lives, compared to family farms.

Nor is it only foreign ownership. Big corporate-owned farms are never good for biodiversity either. There is no human interaction. No footprints in the grass like the proverb: “the best fertiliser for the land is the farmer’s footprints.” It’s all about mega profit for a man in a suit in a big city. The smaller farm is the best for the land, the livestock, and all of us. If governments would see this, as they have in several countries like France and Britain, the countryside would recover and many more people could make a good living. Livestock breeds would be more diverse. We would all be healthier and so would our planet.

Single breeds are invariably used in these operations, losing vital biodiversity. There’s no place for the good old breeds, which are becoming the rare breeds. In western countries with monoculture, livestock breeds are becoming extinct at the rate of knots. In poorer countries, biodiversity and survival of breeds are far healthier.

China is rapidly becoming the biggest owner of our farms. There are also big owners from America, England, Switzerland, Qatar, Greece, Vietnam, Canada, Korea, Philippines, England, Singapore, Jersey, Indonesia, Japan, Netherlands, New Zealand, Denmark, and others. No matter the country, it is the principle that is wrong, Australia for Australians. Small is better than big. It is a bizarre and shocking state of affairs when farming is unviable for us, but profitable for foreigners who own our farms.

Foreign ownership is destroying the family farm, biodiversity, the health and well being of our countryside, ourselves, our livestock breeds, our planet. It is governments who allow this, and who can stop this. Politicians should not be allowed to accept bribes – as “donations” really are – from anyone, let alone big corporations. Let alone foreign ones.

For rare breeds – the old breeds – smaller is better. When a farmer and family look after a farm, the land is healthier, biodiversity flourishes, breeds flourish. The old breeds have so many beneficial aspects it would take a book to fill them. Much better for our health and the health of the land.

Until we get good governance, the best we can do – and it’s a lot - is to shop ethically. Buy local. Don’t buy foreign owned. Buy 100% Australian owned, 100% Australian made. If there is no choice, go without or get something else. Check who really owns brands. Avoid intensive farming. Tell supermarkets where to put their cheap milk. Free range chicken now outnumbers misery chicken in most supermarkets – due to consumer demand. We can do the same for pork, beef, lamb, dairy. A small local cheese is much better than a big cheap one from a foreign-owned dairy where cows are numbers. Quality, not quantity. Go to farmer’s markets. Buy to give our farmers a living, and for our health - you will probably be buying the produce of a rare breed. Go you good thing you!

J. Lane. August 2018.

This article has some good advice on dairy brands

https://www.choice.com.au/food-and-drink/dairy/milk/buying-guides/milk

Who owns Australian farms

https://www.weeklytimesnow.com.au/agribusiness/who-owns-australias-farms-nations-biggest-landholders-of-2018/news-story/479e22e284436477e53e890aa7d6ca38

Dreamy, the Accidental Sheep

By Sue Curliss

This is Dreamy, and Dreamy is the progenitor of the Tukidale sheep. Yes, this one little ram is responsible for the whole Tukidale breed, and this is his story…..

Dreamy was born on November 26, 1966 on the Romney Stud of Malcom and Judy Coop in Tuki Tuki, New Zealand. Dreamy was an accident, possibly caused by the non-closure of a gate by the sawmill workers. He was born way out of season, on the river flats of the Tuki Tuki river and was discovered, along with four other lambs, by Malcolm, whilst he was out riding. Surprised by his find, Malcolm picked the little lamb up and headed for home. If he had any doubts as to Judy’s thoughts about this unusual little lamb, they soon dissipated as he saw her face when he handed her his fluffy charge. In Judy’s own words…..

“…….he was a child’s vision of a dream lamb. Snow white, long, long locks of slightly curling wool. Pink nose and wide-eyed head - even sweet smelling. I cuddled him to me and kissed his then budding horns as I hurried homewards.”

Judy had never seen a lamb quite like Dreamy before. He was a complete character and an absolute individual, but as his horns developed so did his aggressive character and on more than one occasion, Judy had to rescue her young daughter from an apple tree while Dreamy paced below. A young friend was not so lucky and received a broken leg when caught unawares by Dreamy in the paddock. His favourite game was to bang and crash the wrought iron gates with his horns, knowing full well Judy would arrive with treats, a cake tin filled with maize and oats to entice him away. He knew Judy as the bringer of feed and yummy treats and never once tried to butt her. A lesser Shepherdess may have been a bit more concerned by the young ram’s behaviour, but Judy sensed this little guy was special.

As Dreamy grew, his fleece also grew but it was long and straight, unlike any of the other sheep. Malcolm and Judy were visited by the late Dr Dry, the famous New Zealand geneticist, who was responsible for isolating the N gene in the Drysdale sheep. On viewing Dreamy’s progeny, Dr Dry was very excited claiming;

“This fellow has a dominant gene of great value and it is much stronger than the N gene. You must use this sheep extensively.”

Further testing revealed a separate gene in Dreamy’s make-up, the T gene and thus, on the river flats on the banks of the Tuki Tuki river, the Tukidale was born. The T gene was found to be a very dominant gene, in that even a heterozygote sire would produce from any ewe, 50% of hairy progeny. The ability to consistently produce the hairy progeny made the Tukidale a one generation carpet wool sheep. This was a very important find in the days of a rapidly expanding carpet industry and it wasn’t long before a group from Australia imported some of Dreamy’s progeny and the Tukidale story in Australia began, but that i s a whole other story.

s a whole other story.

Dreamy lived a bountiful life and passed in 1977. He was laid to rest under a Red Oak tree. His life is best described by Judy….

“Dreamy sleeps peacefully on in his especially fenced off area, surrounded by the paddocks he knew so well. A rogue, a mutant with a rare genetic difference – possessing almost a hybrid vigour. A once-in-a-lifetime occurrence that happened along our way. An unforgettable V.I.P.”

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

It is the stories like this that make these rare creatures matter. For they, along with their people, their stories and their heritage are all of the utmost importance. Sadly, the Tukidale has just been declared extinct in New Zealand and we have the only remaining flock, here in Australia under the custodianship of Vee and Rene Pols.

The information for this article, photos and excerpts from letters by Judy and Dr Dry are credited with thanks to Bob Eastoe:

The Tukidale Story by Bob Eastoe, published in 1987 by the Tukidale Society of Australia.

Eat them to keep them

by Anne Sim

You have all heard the saying 'Eat them to keep them' when referring to a rare breed. That is something I had believed, but never has it been so well demonstrated with the cockerels I have recently processed for the table.

I have just had a meal from a homegrown cockerel. It is nothing like a supermarket chicken.

This flavour!

The meat is generally somewhat darker. It has a silkiness to it. It has a similarity to lamb shank – that stickiness when it is slow cooked. The breast meat is succulent, not the firmness of the bought sample.

This all started many years ago when I wanted to own a dual purpose bird. Megg Miller suggested the Faverolles breed. These are a French breed and the French eat well so presumed that these would also be good eating. At that time I had never heard of them and there were very few around. I eventually got a pair which laid eggs. For a while, my lifestyle meant that I couldn't have any poultry so they were moved on, and when I was again able, I got Bantam Faverolles. I decided on the Bantam because I knew that they laid eggs much the same size, and ate much less food. They are a breed still in development and do not breed true. There are lines now appearing which seem much better than the ones I purchased. This was a lesson. Actually, the chickens were all over the place in type, size, and colour. And the roosters! Most have finished in the soup pot as up to now they have been the nastiest things around. The only way to feed them was with a length of poly pipe in one hand and feed in the other. If they showed any aggression I would chase them waving the pipe. They were tough but no wonder. Their lifestyle did not go into making tender meat.

I was fed up with these problems so bought some eggs to hatch from the full sized Faverolles. I finished up with rearing two cockerels to five months. This was probably one month longer than desirable but I am learning. Some say the time to slaughter is the weekend after the first crow! Yes, that would be about right.

I like my Faverolles. They are a placid, friendly bird. They put themselves to bed at night, don't wander too far and the real bonus is with the Salmon colour, which is the original colour, they are auto-sexing. This means that the cockerels and pullets have a different colour. If you don't want to rear cockerels they can be identified very early.

When I finished dressing them they were covered and rested in the fridge for three days, then cut into portions for the freezer. Now we eat one or two meals a week of the most delicious chicken. The carcasses have made beautiful soup, with a much richer and stronger flavour. On bought chicken, the wing consists of a tip, a wingette and a drumette, all quite tiny pieces. The carcass has a different size ratio of cuts. Tonight our meal was two drumettes each which was a great serve. Of the bought ones that wouldn't have made a snack. The breasts on these were not such a big piece. A commercial breast I slice horizontally in half, but with these, I only flatten. Not as big, but they make a the lovely-est schnitzel.

And I will be trying to breed enough next year for me to eat chicken often and not have to buy any. I have no idea of the cost to rear, but I suspect that it is more than the $10.00 of the Supermarket chicken.

But then that flavour has no price.

Australian livestock in court

How many cows fit in a courthouse? While swotting DNA for our gene-bank proposal I came across what appeared to be an alarming federal court case, dragged over two years with appeal and continuing into this month, March 2018. About the patenting of cattle DNA. I rushed to investigate - surely no-one could patent cattle DNA? Or parts of it? could they?

A large American company, Branhaven, with a subsidiary in Australia, Cargill, apparently wants to patent some cattle DNA in Australia. In principle, such a patent could extend to all livestock. Basically, such a patent would be a cash cow. The profits would go to America. Mind you, whilst it was difficult to grasp exactly what Branhaven wanted with this patent, one found no-one else was entirely sure either. Anguished press reports, indignant vested interests, treading in fresh cow pats - the bellowing was deafening! It involved a patent on DNA components (do I get a Guernsey for that?). For example, there is a gene for meat tenderness – of interest, already patented by MLA (Meat & Livestock Australia), the CSIRO and an MP or two.

"Patent-eligible subject matter under Australian law is required to be an artificially created state of affairs having economic significance." 1

Many farmers of course, routinely test animals for useful genomes, to select ideal breeders. Most of this work is aimed at improving commercial beef and dairy production, however, is applicable to all livestock.

Naturally occurring DNA cannot be patented in Australia but there are several strange twists. The argument is that to discover and use isolated parts of DNA is not a natural process, but artificial, thus the methods and discovery are in the manner of the invention, for the results can be subject to artificial manipulation which is then an invention in itself. Inventions can be patented. They claim microsatellites on markers, like SNP’s – single nucleotide polymorphisms, which are the building blocks of DNA – are artificially isolated to be identified, even although they are naturally occurring. Therefore, once discovered and identified, a particle of DNA could be patented - although where the invention comes into this is baffling. One thinks of the tenderness gene already being granted a patent. The holder of these patents can then use these genes for cloning and basically charge for their use.

Justice Beach concluded, in essence, MLA’s appeal against the patent was in part upheld for sound reasons, and in part not upheld, for lack of same. He made suggestions to Branhaven to amend their application. Basically - to be clear, to define the invention, and to define the utility of the patent. In other words, cut through the bulldust. And to MLA to improve their weaponry. No need for a poll on that.